The UConn Huskies and San Diego State Aztecs will face off in tonight’s NCAA men’s basketball national championship, capping off an upset-filled March Madness. Huskies guard Jordan Hawkins has been instrumental in leading UConn to its first Final Four appearance in nine years. Dunkin’ saw that—before March Madness began, the New England–headquartered doughnut chain signed a “name, image, and likeness” deal with Hawkins, UConn’s second-leading scorer this past regular season.

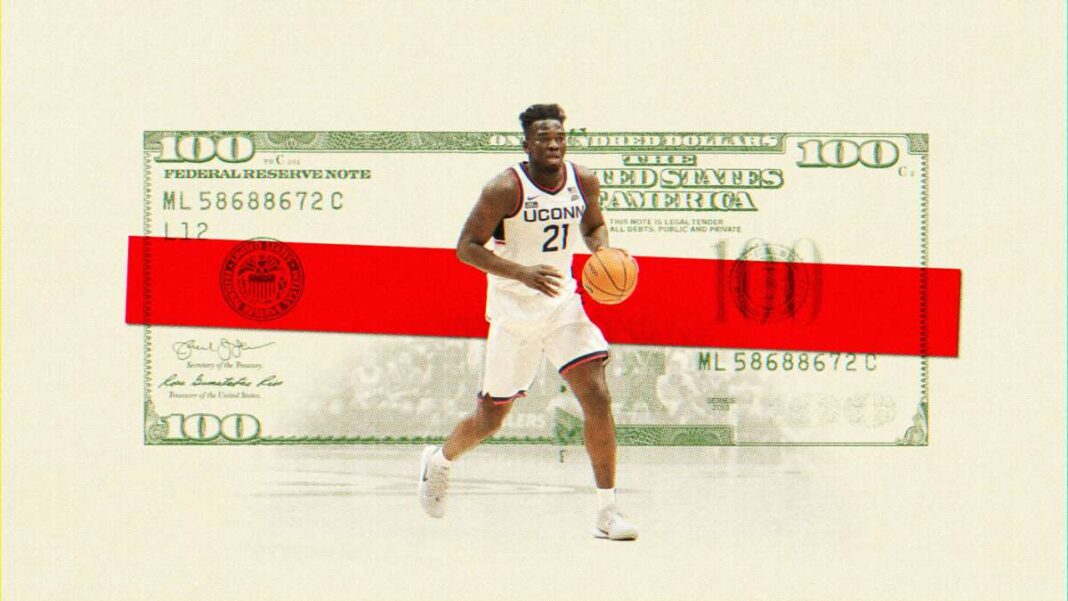

It would make perfect sense for Hawkins’ teammate Adama Sanogo, UConn’s star forward and top scorer this year, to benefit from a name, image, and likeness deal too. But thanks to ambiguity in U.S. immigration law, Hawkins, a U.S. citizen, can profit from sponsorship deals, while Sanogo, a Malian national, cannot. It’s an issue that affects several standouts in this year’s March Madness, including Princeton’s British forward, Tosan Evbuomwan, and Florida Atlantic’s Russian center, Vladislav Goldin.

“A player of Adama’s caliber deserves it for everything he’s done in his career and everything he’s done for UConn basketball,” said UConn coach Dan Hurley. “You would hope that would change, but that’s obviously something that, again, Homeland Security and government, and that stuff doesn’t tend to move super quickly.”

The NCAA used to bar all college athletes from making money off their names, images, and likenesses. But since a 2021 rule change, they have been eligible to earn money through endorsement deals, social media activity, and paid appearances. The NCAA had long viewed college athletes as amateurs, but the policy change—quite sensibly—recognized that students deserved to be paid as professionals. In the first year of name, image, and likeness arrangements, Opendorse, a technological platform for these deals, estimated that college athletes made $917 million. Three-quarters of all NCAA athletes had engaged in the market from July 2021 to July 2022.

But international students largely operate in “a gray zone” in American immigration law when it comes to endorsements, says James Hollis, an immigration attorney at Siskind Susser, PC who has previously advised professional sports organizations on visa matters. “Students, schools, and their lawyers are all operating within the standard student visa framework,” Hollis tells Reason. College athletes are largely in the U.S. on F-1 visas, which place tough restrictions on work. “The student visa rules say that student athletes can work part time on campus, can work if authorized as part of the curriculum…and can work after one academic year if they can demonstrate they’re experiencing economic hardship,” says Hollis.

None of that fits neatly into the name, image, and likeness apparatus. “Some foreign student athletes have been able to obtain O-1 extraordinary ability visas authorizing them to work, study, and compete,” says Hollis. Others have arranged completely “passive deals where they receive income but do nothing that could be considered work while in the United States.” According to Hollis, “the safest path has been to sign deals and then do the work to promote the NIL [name, image, and likeness] content” strictly while outside the United States.

Two years after the NCAA rule change, the Biden administration still hasn’t offered definitive guidance that would allow foreign college athletes to make money like their native-born peers. On a more basic level, this leaves foreign athletes wondering whether certain activities might be violations of their student visa terms.

According to ESPN, just one of the eight teams that played in the men’s and women’s Final Fours didn’t have at least one international student player. UConn has four. Per the NCAA, “roughly one out of every eight athletes across all Division I sports is from a foreign country,” leaving a gaping hole in the system that allows student-athletes to sign often lucrative sponsorship deals. Visa term violations can be dire—potentially as severe as deportation.

“Overall, it is a strange system for foreign national athletes that seems to mimic the major issue that NIL deals were created to push back against in the first place,” Hollis explains. “Student athletes are constantly taking part in activities that would in another context be considered work.” The Department of Homeland Security “does not seem to have a problem with foreign student athletes having their photos taken to promote the university that they attend or for purposes of advertising a major televised tournament,” he notes.

“The path to changing the rules for foreign student athletes is a hard one,” Hollis contends, but he suggests a few policy changes that could level the playing field between foreign- and native-born college players. The government could issue guidance “telling schools and student athletes exactly what does and does not count as work for purposes of NIL deals,” since the F-1 student visa, created in 1952, generally doesn’t authorize work. “A better solution would be having Congress amend the law to add a special category for foreign student athletes that specifically authorizes them to engage in NIL deals.”

“Until one of these happens, foreign student athletes will have to continue to contort themselves around a law that was created in a different historical moment,” says Hollis, “and will continue to be at a significant disadvantage to their U.S. athlete peers.”