By Myles BurkeFeatures correspondent

Getty Images

Getty Images

In an exclusive clip from the BBC Archive, watch Nelson Mandela speak about his historic release from prison, which was a watershed moment for South Africa in its transition to democracy.

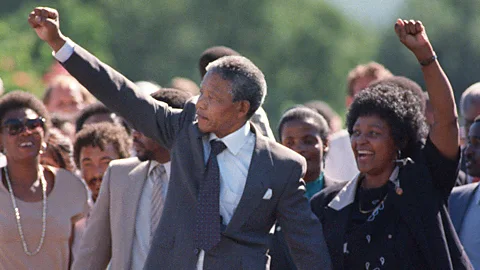

On 11 February 1990, at 16:14 local time, Nelson Mandela, once South Africa’s most wanted man, walked out of Victor Verster Prison hand-in-hand with his then wife Winnie, after spending 27 years behind bars. Huge crowds had waited for hours in the sweltering heat in anticipation of catching sight of him. Mandela had been largely hidden from view during his long years of imprisonment. The government had not released any photos of him while he had been in captivity, in the hope of curbing his growing fame since his conviction.

More like this:

– The man behind the Rubik’s Cube

Despite this, in the years that followed he had become an international symbol of resistance against the apartheid regime that oppressed South Africa’s black population. By 1990 he had taken on an almost mythic status. Hundreds of supporters thronged the street outside the prison, many of them waving the green, gold and black flags of recently unbanned African National Congress (ANC). The crowd broke out into euphoric cheers as the Mandelas emerged, determined and unbowed, and punched the air in a victory salute. His release that day was a moment of history. But it almost didn’t happen.

Born in 1918 in the eastern Cape of South Africa, Mandela had led the ANC’s nonviolent protest against the apartheid legislation which enforced a racial hierarchy that subjugated South Africa’s black majority. It governed every aspect of life for non-white South Africans who were subjected to forced removals, “pass laws” that restricted their free movement and the denial of their basic human rights. This had made Mandela a frequent target of the all-white government who sought to harass, intimidate and, at times, arrest him to undermine his efforts to organise boycotts and strikes against the regime.

What proved to be a turning point for him was the “horrific affair” of the Sharpsville massacre in 1960, when 69 black people were shot dead by police while protesting the pass laws. “People had tended to feel that we had done everything in our power, to try all options open to us,” Mandela told Joan Bakewell in a BBC interview in 1990. “Not only was there no improvement as far as our living conditions were concerned. But the government took advantage of our commitment to nonviolence and decided to be even more vicious. It was under those conditions that we decided to resort to violence.”

When we were sent to jail, we had the feeling that we had been victorious. And that the people who were actually the accused were the government itself – Nelson Mandela

This triggered a campaign of economic sabotage by the ANC that targeted infrastructure rather than people and led to Mandela’s arrest. He, along with several other men, was charged with sabotage, treason and violent conspiracy. Speaking from the dock in the courtroom, Mandela articulated his fundamental beliefs with conviction and defiance. “I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die,” he said.

Gruelling conditions

In 1964, Mandela received a life sentence, narrowly escaping the death penalty. “Although we were sentenced and sent to jail, we felt that we had come out head and shoulders above the government. Our defence was an attack on government policy, right from the time when they asked us, ‘Are you guilty?”http://www.bbc.com/”No we are not guilty, it is the government that is guilty.’ And, therefore, when we were sent to jail, we had the feeling that we had been victorious. And that the people who were actually the accused were the government itself,” he said.

In History

In History is a series which uses the BBC’s unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today.

Mandela spent 18 years of his prison term on Robben Island. He was held in a small cell without any plumbing, sleeping on a mat on the stone floor. During the day he did gruelling work labouring at a limestone quarry. “Lime is a very difficult thing, you know, to dig because it is in layers. It is between layers of rock, hard rock.”

The authorities took efforts to keep him hidden from the world. Once a year he was allowed a visitor but only for 30 minutes. Despite his mother dying in 1968 and his eldest son being killed in a car crash less than a year later, he was not allowed to attend their funerals. However, he still managed to smuggle out letters and advocate for the ANC.

In 1982 he was moved to Pollsmoor Prison in Cape Town, where the damp conditions contributed to him being hospitalised with tuberculosis in 1988. The apartheid government throughout this time periodically made offers to release him, but the freedom that was offered was always subject to government conditions, which Mandela resolutely refused. In 1989, FW de Klerk was elected South African president. The following year, he announced that he was lifting the ban on the ANC and ordering Mandela’s imminent release from prison.

On 10 February 1990, President De Klerk met Mandela to tell him he was going to be released the next day. This time it was an unconditional release. He would be a free man. But to President de Klerk’s surprise, Nelson Mandela’s response seemed muted. “I thanked Mr de Klerk, and then said that at the risk of appearing ungrateful I would prefer to have a week’s notice in order that my family and my organisation could be prepared,” he wrote in his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom.

Taken aback, President De Klerk, after briefly consulting with his advisors, came back to say he would, in fact, have to insist that Mandela leave prison as planned. Mandela conceded and the two shared a drink. He walked to his freedom the next day and stepped into history. Three years later Mandela, as leader of the ANC, became South Africa’s first black and democratic president.

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.