Malthusianism is just so damned tiresome. The constant stream of predictions that a growing human population will soon crash because we are about run out of food and/or other resources has always failed to come true. Now, a new People and Planet report by researchers operating as part of the Earth4All initiative of The Club of Rome projects in two different scenarios—Too Little Too Late versus Giant Leap—that the world population will peak around the middle of this century. Good news, but the authors just can’t help inflecting their report with a touch of good old-fashioned Malthusianism. Call it Malthusianism-lite.

Eponymously, Malthusianism begins with the claims made by the 18th-century economist Thomas Robert Malthus in his 1798 An Essay on the Principle of Population. “Population,” Malthus famously asserted, “when unchecked, increases in a geometrical ratio. Subsistence increases only in an arithmetical ratio…. This implies a strong and constantly operating check on population from the difficulty of subsistence.” This differential in the growth rates of population and food supplies meant that some portion of mankind would always be on the verge of starvation.

What Malthus did not foresee was how modern science coupled with the dynamism of increasingly free markets would produce over the next two centuries what economist Deidre McCloskey has called the Great Enrichment. Entrepreneurial human ingenuity makes it possible to produce food at an exponential rate that outstrips population growth, resulting in more calories per person.

The most notoriously wrong modern prophet of Malthusian doom is Stanford biologist Paul Ehrlich. My public crusade against Malthusian stupidity began with my 1990 Forbes article, “Doomsday Rescheduled,” in which I reviewed Paul and Anne Ehrlich’s book The Population Explosion. “One thing seems safe to predict: starvation and epidemic disease will raise death rates over most of the planet,” they asserted in the book. I pointed out that this was a follow-up to Paul Ehrlich’s failed prediction made 22 years earlier in his 1968 The Population Bomb, “The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s the world will undergo famines—hundreds of millions of people are going to starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked on now. At this late date nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate.” That didn’t happen.

Unchastened by failed prediction after failed prediction, modern Malthusians remain entranced by the simplicity of their model. Consider the overpopulation twaddle peddled by Daniel Quinn’s telepathic gorilla in his 1995 novel Ishmael and Jared Diamond’s 2005 shoddy narrative of doom, Collapse.

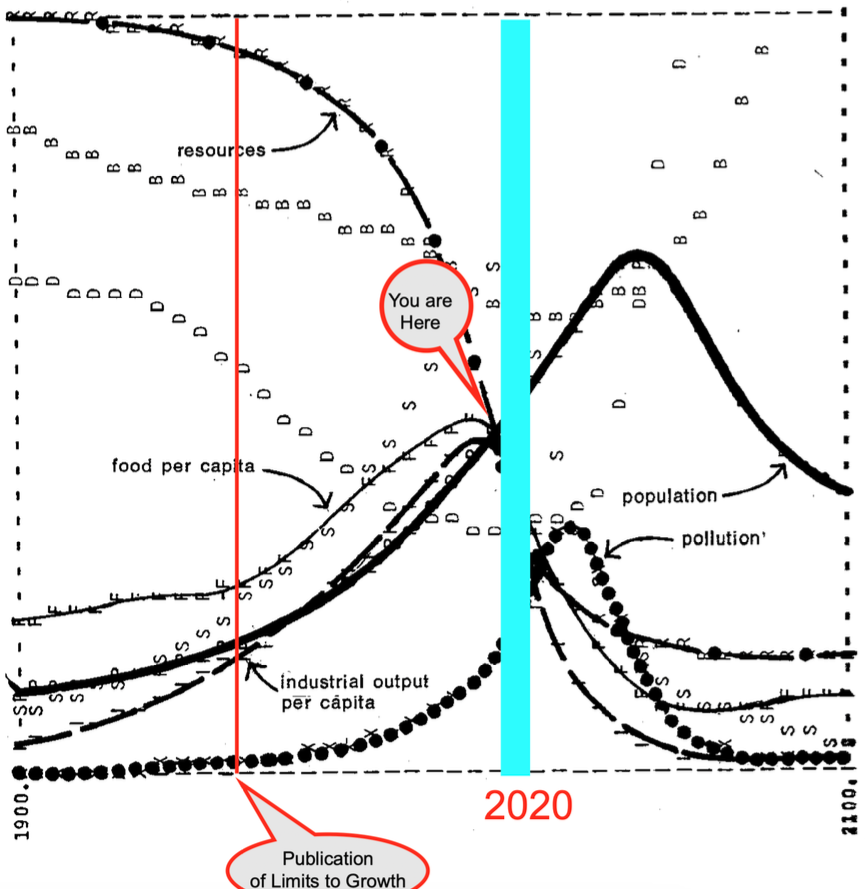

Keep in mind that the new People and Planet report has been commissioned by the same The Club of Rome that promoted the notorious The Limits to Growth report back in 1972. “For 50 years, since The Limits to Growth report and the 1972 UN Stockholm summit, the world has ignored the risk of system collapse,” (emphasis theirs) admonishes the Earth4All initiative. The 1972 report concluded, “The basic behavior mode of the world system is exponential growth of population and capital, followed by collapse.” In the “standard run” of The Limits to Growth computer model:

“Food, industrial output, and population grow exponentially until the rapidly diminishing resource base forces a slowdown in industrial growth. Because of natural delays in the system, both population and pollution continue to increase some time after the peak of industrialization. Population growth is finally halted by a rise in the death rate due to decreased food and medical services.”

The 1972 report projected that exponential consumption would deplete important nonrenewable resources such as oil, natural gas, copper, tin, and lead before the year 2000. That didn’t happen.

Just over 50 years later, the new People and Planet report eschews “hard limits to growth beyond planetary boundaries.” The nine planetary boundaries used in the new report are derived from a 2009 Nature article in which researchers aimed to identify “a safe operating space for humanity.” The new report finds that humanity has already “overstepped” six of those boundaries: global warming, biodiversity loss, ozone depletion, air pollution, land use change, and nutrient overloading. The People and Planet report concludes that by 2020 for those six boundaries, “humanity was already exploiting more than what is sustainable in global ecosystems, along multiple dimensions.” Ocean acidification, freshwater use, and novel entities (formerly known as chemical pollution, but now related to plastic wastes) are not quantified and so not considered.

The salience of the planetary boundaries hypothesis is highly questionable. A 2012 analysis by the eco-modernist Breakthrough Institute pointed out that six of the planetary boundaries—land use change, biodiversity loss, nutrient overloading, freshwater use, air pollution, and chemical pollution—do not have planetary biophysical thresholds; their effects essentially regional and local. Consequently, the analysis finds that “there are no global tipping points beyond which these ecological processes will begin to function in fundamentally different ways than they do at present or have historically.” The upshot is that “there is little evidence to support the claim that transgressing any of the six non-threshold boundaries would have a net negative effect on human material welfare.”

In both of the new Earth4All scenarios, there is no global food shortage, no explicit mention of imminent nonrenewable resource depletion, and world population peaks and gradually falls due to demographic choices, not through a Malthusian collapse.

“According to our results across all simulations for both scenarios, the primary issue is not overpopulation in comparison with available resources, but rather the current (too) high consumption levels among the world’s richest quarter,” assert the authors. “Or, put even more concisely: humanity’s main problem is distribution rather than population” (emphasis theirs).

Nevertheless, the Earth4All report’s Too Little Too Late—”decision-making as usual”—scenario is a kind of Malthusianism-lite, detailing “a situation characterised by ever-increasing risks for having triggered irreversible declines in Earth’s life-supporting systems and all its associated ecosystems.” Whereas the Giant Leap scenario “represents a pathway towards fully returning human pressures on the planetary systems to the safe zone in civilisation’s long-term view, hopefully before irreversible planetary declines are triggered.”

In the Too Little Too Late scenario, global population peaks at around 8.8 billion in the 2050s falling to around 7 billion by 2100, and average annual global per capita income reaches $42,000. Global average temperature increases to 2.5 degrees Celsius above the 1850-1900 average. In the Giant Leap scenario, population peaks at 8.5 billion in the 2050s and declines to around 6 billion by 2100, and average annual global per capita income reaches $51,000. Global average temperature rises to 2 degrees Celsius over the 19th-century baseline. Both ozone depletion and air pollution in 2100 are below the posited planetary boundary thresholds, and the nutrient overloading boundary is still exceeded in the Too Little Too Late scenario. With respect to future man-made global warming, the world is likely already on track to keep the increase in average global temperature at around 2 degrees Celsius over the 19th-century baseline.

So what “extraordinary turnarounds” are allegedly needed to move from “decision-making as usual” to the Giant Leap? They are ending poverty, addressing gross inequality, empowering women, making food systems healthy for people and ecosystems, and transitioning to clean energy. The People and Planet team aims to end poverty by having the International Monetary Fund allocate $1 trillion annually to low-income countries for green jobs; reduce inequality by increasing taxes on the richest 10 percent until they take less than 40 percent of national incomes; empower women by providing them access to education; incentivize farmers to adopt regenerative agriculture and engage in sustainable intensification; and with respect to energy, immediately phase out fossil fuels while spending $1 trillion annually on scaling up new renewables.

As it happens, “decision-making as usual” has already been furthering those trends. As population more than doubled since 1972, average per capita global gross domestic product in constant 2015 U.S. dollars has risen from $5,200 in 1972 to $11,000 in 2021. With respect to absolute poverty, the World Bank reports that in 1972 nearly half of the world’s people lived on less than $2.15 per day. That has fallen to just over 8 percent in 2019.

Assuming an average 3 percent annual growth rate, the world’s GDP would increase from $100 trillion now to $974 trillion by 2100 yielding per capita GDP for 7 billion people of nearly $140,000 annually. Assuming just a 2 percent growth rate, per capita GDP would rise to around $66,000 annually. And this does not take into account the technologically advanced products and services that will be available eight decades hence. It is notable that these rough calculations are well above the People and Planet projections by average per capita incomes in 2100.

For the authors, overpopulation is not the issue; inequality is.

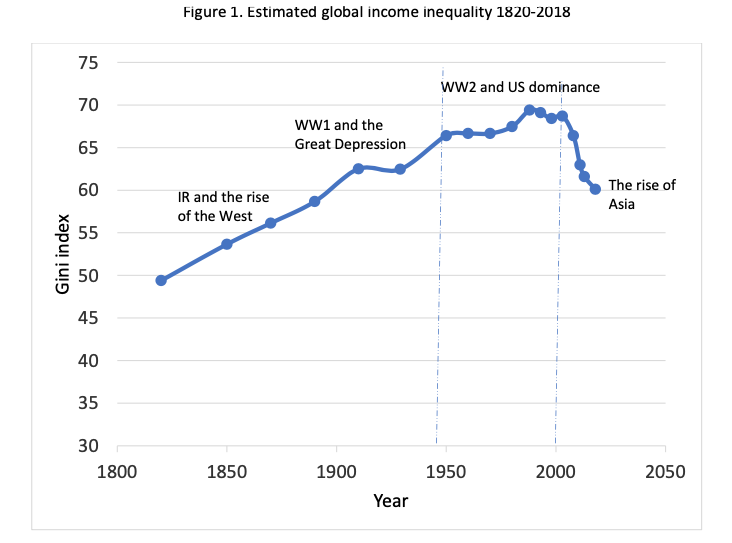

However, income inequality has been falling among nations. That is, poorer places are getting richer faster than already well-off countries.

Notably, City University of New York economist Branko Milanović observes that income inequality has been rising within “many large countries including the United States, China, Russia, India and even the welfare states of continental Europe.” The remedy recommended by the authors is to increase taxes on the richest 10 percent until they take less than 40 percent of national incomes. As it happens, according to the World Bank, there are very few countries in which 40 percent of national income goes to the top 10 percent. (The U.S. figure is 45.6 percent.)

The authors clearly want much of the taxes collected to be redistributed to poor countries as foreign aid, e.g., $1 trillion per year to create green jobs. There is a robust debate over the effectiveness of foreign aid with respect to boosting economic growth, but not too surprisingly, I find Institute for European Studies economist Miroslav Prokopijević’s argument that “foreign aid fails because the structure of its incentives resembles that of central planning” persuasive.

Education is one good measure of the increasing empowerment of women. Among other things, it correlates with increased reproductive choice and access to employment outside of their households. While obviously not nearly enough, the percentage of females globally receiving primary education rose from 65 percent in 1972 to 88 percent in 2018, and secondary education increased from 38 percent to 76 percent.

The People and Planet report wants to subsidize “regenerative agriculture” as a way to make food production “healthy” for ecosystems. One big problem is that there are no consistent definitions of regenerative agriculture. It’s largely just a term used to denigrate also ill-defined, but rhetorically disfavored, conventional agriculture. Considering that agriculture is the most extensive way that humanity alters natural landscapes, it is good news for healthy ecosystems that farmland peaked around the year 2000, leaving more land for nature. Instead of plowing down more land, farmers around the world are intensifying their production, thus growing more food on less land. Oddly, in both the Too Little Too Late and the Giant Leap scenarios, the amount of cropland continues to increase up to 2100.

The final Giant Leap policy recommendation is to incentivize the global transition to clean energy sources by which the authors mean chiefly solar and wind power. (Nuclear is not mentioned.) They specifically recommend beginning the process of electrifying everything by means of immediately tripling investments to more than $1 trillion per year in new renewables. Interestingly, in January 2023, Bloomberg New Energy Finance reported that “global investment in the low-carbon energy transition totaled $1.1 trillion in 2022 – a new record and a huge acceleration from the year before.” The International Energy Agency projects that renewables will become the largest source of global electricity generation by early 2025, surpassing coal. It may not be as fast as the authors demand, but the energy transition is already well underway.

To sum up: The world and the state of humanity are not where we want it to be, but global poverty is rapidly falling, inequality between countries is declining, women are gaining greater personal autonomy, peaked farmland is sparing more land for nature, and renewable energy sources are being briskly deployed.

Back in 1972, The Limits to Growth report commissioned by The Club of Rome was thoroughly Malthusian: Unless humanity changed its profligate ways, population collapse loomed. The Club’s new People and Planet report amounts to Malthusianism-lite. Tiresome still, but better, I guess.