By Adam ScovellFeatures correspondent

Getty Images

Getty Images

One hundred years ago, wealthy Chicago students Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb brutally murdered 14-year-old Bobby Franks. Why is popular culture obsessed with this horrific case?

It took a lot to shock the US in the 1920s. The country was still reeling from the aftermath of World War One. The age of Prohibition led to a rapid increase in violent organised crime. And the decade was bookended by two of the worst economic slumps in history: the Forgotten Depression of 1920-21 and the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

More like this:

– A horrifying true-crime classic

However, the US was indeed shocked in 1924 by two affluent students in Chicago, Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, and their attempt at the so-called “perfect crime”: a plan in which they believed they could achieve both the apparent thrill of committing a murder and the even greater thrill of not being caught.

Getty Images

Getty Images

What initially started as intellectual curiosity arising from the philosophy they were reading ended in the brutal murder of a child. One hundred years on, the US’s shock still rings out, the crime having had a lasting impact on culture, across film, theatre, literature and television – resulting in works including the classic Alfred Hitchcock film Rope.

The facts of the case

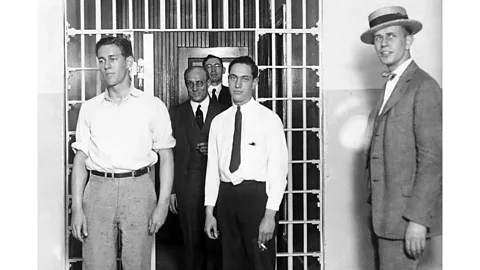

Leopold and Loeb were childhood friends from well-to-do families. At the time of committing their crime, Leopold, 19, had just graduated from the University of Chicago and was hoping to be accepted into Harvard Law School while Loeb, 18, was studying history at the University of Chicago Law School. On 21 May 1924, after months of planning, the pair lured 14-year-old Bobby Franks, a distant cousin of Loeb’s, into a car. One of the pair killed him, though it’s still debated which one, before they hid his body in a remote area.

The pair then quickly put their plan of subterfuge into action, laying false clues to confuse the police, in particular a fake ransom demand to Franks’s family. But, quickly, the plan fell apart: the body was found just the following day, 22 May, which was sooner than expected, so the ransom ploy failed to convince authorities. Unbeknownst to the killers, Leopold also left a pair of uniquely designed glasses at the crime scene which were traced back to him.

I think it continues to fascinate artists because it defies our ideas about ‘motive’ and about what it means to be ‘civilised’ – Nina Barrett

Under pressure, Leopold confessed to the crime and implicated Loeb as his accomplice. It was the motive behind the murder that shocked the nation, however. Leopold and Loeb presented their crime as an intellectual exercise, driven by their belief in the concept of the Übermensch – the superman who transcended conventional human morality – as explored by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. They saw themselves as thrill-seeking superior beings who could reach Übermensch status through the murder.

Their trial began in July 1924 and quickly became a media sensation. Clarence Darrow, a renowned defence attorney, took on the case and argued against the death penalty. Leopold and Loeb pleaded guilty, and the judge eventually sentenced them to life imprisonment plus 99 years.

The pair went to separate prisons, and their families disowned them. Loeb was later killed by a fellow inmate in 1936, while Leopold was eventually paroled in 1958 and lived the remainder of his life in relative anonymity, publishing some writing and dying in 1971.

The Leopold and Loeb case, as it became known, left a profound mark on US society and the legal system. It was dubbed by the newspapers the “crime of the century”, and sparked discussions around crime, punishment, and rehabilitation.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Author and journalist Nina Barrett studied the case in depth for her book The Leopold and Loeb Files (2018). With extensive access to documentary evidence, she believes the reason for the enduring interest in the case is clear. “I think it continues to fascinate artists because it defies our ideas about ‘motive’ and about what it means to be ‘civilised’,” she tells BBC Culture, adding that “despite its having received more scrutiny than possibly any other murder case in modern memory, no one has ever produced a satisfactory explanation of why Leopold and Loeb thought murdering a neighbourhood boy would be thrilling”.

The crime’s cultural impact

The earliest example of its macabre cultural influence is a British rather than American one, tellingly. Come the late 1920s, the US wasn’t quite ready to produce creative retellings of the crime just yet. However British author Patrick Hamilton certainly did have ideas as to why the pair did it. Like many struggling authors, Hamilton liked sitting in cafes and pubs. It was during the long days staving off a growing dependency on alcohol that he began to draft what would become his breakthrough play, Rope, inspired by the Leopold and Loeb case. Hamilton’s work often reflected the psychological depths of individuals, especially in later novels such as Hangover Square (1941): with an eye for the seedier, hopeless side of human life, the killing made perfect raw material.

First premiering on 3 March 1929 at London’s Strand Theatre, Rope was an instant success. Set in upmarket Mayfair rather than Chicago, and recasting Leopold and Loeb as Oxford students, Wyndham Brandon and Charles Granillo, Rope more than echoes the original Franks murder. Hamilton changed the narrative, however, so that the victim is a fellow classmate of the two protagonists rather than a child, while the theatrical staging had the body on stage at all times, hidden in a trunk. Hamilton’s skilful character development chilled audiences, as did the daring presentation of the entire play in one continuous act without intermission.

Rope is the intellectual and moral centre of Hitchcock’s work. Instead of looking askance at murder, he stared right at it – Mark Cousins

“I have gone all out to write a horror play and make your flesh creep,” Hamilton suggested in his own preface. “It is a thriller. A thriller all the time, and nothing but a thriller.” Hamilton was doing himself an injustice. The play delved deep into the evil, intellectual motivations of men who see themselves as above society. With World War Two around the corner, a war in which a similar bastardisation of Nietzschean ideology by the Nazis powered its atrocities, Rope was anything but a simplistic thriller. The play’s West End popularity swiftly led to a New York production, at the Theatre Masque on Broadway, where it was retitled Rope’s End.

Next it made its way to the small screen when, in 1939, the play was adapted by the BBC. Another production of the play was subsequently broadcast in 1947, with Dirk Bogarde as one of the murderers, before Alfred Hitchcock created his own big-screen version in 1948.

Hitchcock’s interpretation

Hitchcock himself was well acquainted with true crime, so it’s unsurprising Rope appealed to his morbid sensibilities. He demonstrated his credentials with the genre early on in his career, when he adapted Marie Belloc Lowndes’s Jack the Ripper-inspired novel The Lodger in 1927. Later, Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt (1948) was based on prolific serial killer Earle Nelson, while Frenzy (1972) was adapted from Arthur La Bern’s novel Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square (1966), which itself was inspired by the so-called “Jack the Stripper” murders in 1960s London. Perhaps most famously, Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) was adapted from a short story by Robert Bloch, which echoed the macabre crimes of Ed Gein. In other words, a number of Hitchcock’s most celebrated films derived from true crime, albeit several layers removed.

Director and film historian Mark Cousins recently reconsidered Hitchcock’s work for his film about the director, My Name is Alfred Hitchcock (2023). “Rope is the intellectual and moral centre of Hitchcock’s work,” Cousins suggests. “He wasn’t trying to be funny or amuse. Instead of looking askance at murder, in Rope he stared right at it. He didn’t lighten his form.”

Even though Rope tries to tack on a suitably moral ending, I feel that it also glamorises what they’ve done – Nina Barrett

The film had an added frisson of risk in the – then illegal and heavily implied – homosexual relationship between its Leopold and Loeb ciphers Philip (Farley Granger) and Brandon (John Dall). Bringing Rope to the screen with help from screenwriters Hume Cronyn (also an actor who appropriately played a true crime enthusiast in Shadow of a Doubt) and Arthur Laurents, Hitchcock fleshed out Hamilton’s play with a larger cast of characters, as well as casting James Stewart as Rupert Cadell, the pair’s former teacher and the film’s moral gauge. Cousins considers one moment from the film especially poignant – when Stewart says to the duo “you’ve made me ashamed at every concept I’ve ever had about superior and inferior beings. But I thank you for that shame.”

Rope was also incredibly experimental for Hitchcock: not only was it his first film in Technicolor but, inspired by its theatrical presentation on television, he decided to create the illusion of it being filmed in one simultaneous take. Though it was actually made up of 10 takes, the result still made for a unique, nightmarish film.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Rope turned out to be one of Hitchcock’s most effective films, but the uncomfortable questions it raised led to a mixed reception. As Chicago Tribune critic Mae Tinne wrote: “If Mr Hitchcock’s purpose in producing this macabre tale of murder was to shock and horrify, he has succeeded all too well”. She later warned readers that it was “not recommended to the sensitive”. The public took note as the film did poor box office, its commercial failure compounded by various states and cities banning the film. However, Barrett understands the unease that surrounded Rope. “As a film, not just as a story, I personally find it very disturbing, because even though it tries to tack on a suitably moral ending, I feel that it also glamorises what they’ve done.” Nevertheless, the film’s infamy didn’t stop other creatives from looking to the Leopold and Loeb case for inspiration. In fact, it seemed to spur them on.

It was in the 1950s when Leopold was first approached in prison by author Meyer Levin. A contemporary of the murderers and intrigued by the case for a number of years, Levin approached Leopold with the idea of turning the story into a novel. Leopold told Levin he didn’t want his crime fictionalised, instead suggesting Levin help him with his memoir, but Levin went ahead anyway, much to Leopold’s frustration.

A closer retelling

The novel was Compulsion (1956), a thriller which stayed uncomfortably close to the truth. Unlike Rope, Compulsion was set in Chicago. It followed the intellectual manoeuvrings of the two characters, this time renamed Steiner and Strauss, their romantic relationship together and their crime, followed by the drama of the trial. Leopold was more than unimpressed on finally reading a copy, not least as Steiner, his fictional cipher, was explicitly shown to be both the instigator and perpetrator of the crime.

“The impact of Compulsion on my mental state was terrific,” Leopold later wrote of the book. “It made me physically sick, I mean that literally. More than once I had to lay the book down and wait for the nausea to subside.”

This case, unlike your run-of-the-mill true crime story, has really attained the status of myth – Nina Barrett

The book became a best-seller and Compulsion quickly found its way to the stage, before once again Hollywood smelled blood in the water, getting accomplished director Richard Fleischer to adapt it for film.

Fleischer would develop a strong relationship with true crime over the years, later making what is still perhaps the most effective true crime film ever made, 10 Rillington Place (1971). With a cast that included Orson Welles as attorney Jonathan Wilk (a fictional version of Darrow), the film was a hit in spite of Leopold attempting to block the film’s production. But years later, in 1970, Leopold brought a case against Levin, his publishers and the film’s distributors for invasion of privacy. However an Illinois judge rejected the murderer’s case that, because the book and subsequent film may have mixed fact with fiction, it was damaging to the plaintiff’s character. The judge declared that, in Leopold having been found guilty of the supposed “crime of the century”, there should be little sympathy for his privacy.

Leopold’s various attempts to stop Compulsion were one of the earliest examples, if not the earliest example, of a figure involved in a case condemning its true crime media representation – though typically today it is victims’ families who condemn true crime, not the perpetrator.

Alamy

Alamy

For better or for worse, the influence of the case has continued to pervade popular culture. More books inspired by it appeared quickly in the wake of Compulsion, such as James Yaffe’s novel Nothing but the Night (1957), and Mary Carter’s Little Brother Fate (1957), a collection of three stories inspired by infamous US murder cases of the 1920s. In film and television, there has been Tom Kalin’s Swoon (1992), which is the most recent direct dramatisation of the case. Arch sleuth Columbo got in on the action, too, in the 1990 episode Columbo Goes to College, which took clear inspiration from Leopold and Loeb in its story about the detective bringing two students to justice. As recently as 2019, the murderers’ Nietzsche-inspired psychopathy was the inspiration for the central storyline of the third season of the hit US crime show The Sinner, and no doubt more retellings will appear as the century’s true crime gluttony continues.

So why does this grim case continue to inspire so much art? Barrett has a stark answer. “This case, unlike your run-of-the-mill true crime story, has really attained the status of myth. And it did so very quickly, because of all the very profound questions it raised, almost all of which are difficult if not impossible to answer,” she concludes, referring to the terrible fascination with murder whose motives are utterly beyond general human comprehension. It certainly does seem that the crime of the 20th Century is determined to live on into the 21st.

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.