“I’m under no illusion that humanity will completely eradicate the racial tribal instinct or racism or bigotry itself. But I feel that colorblindness is the North Star that we should use when making decisions,” argues Coleman Hughes, a writer and podcaster who specializes in race, ethics, and public policy.

Hughes’ forthcoming book, The End of Race Politics: Arguments for a Colorblind America, calls for returning to the original ideals of the American civil rights movement, arguing that “our departure from the colorblind ideal has ushered in a new era of fear, paranoia, and resentment.” After some staffers and audience members declared his recent TED talk “hurtful,” for example, Hughes believes TED deliberately downplayed the online version of the presentation. “TED,” Hughes concluded, “like many organizations, is caught between a faction that believes in free speech and viewpoint diversity and a faction that believes if you hurt my feelings with even center-left, center-right, or, God forbid, right-wing views, you need to be censored.”

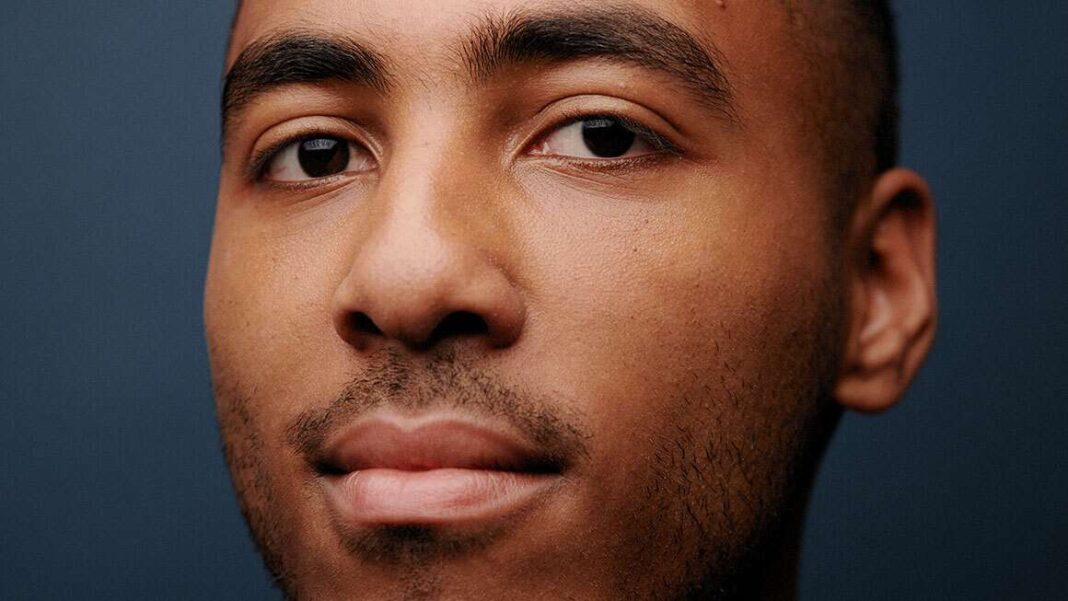

In November, Reason‘s Nick Gillespie spoke with Hughes about colorblindness, free expression, and whether class or race is the more accurate indicator of being disadvantaged in the U.S. today.

Reason: What is the case for colorblindness?

Hughes: We are human beings. Despite the philosophies of people like Michel Foucault and others who I know you have some admiration for, there is such a thing as human nature. One of its uglier elements is tribalism: the tendency to form tribes based around ethnicity or race—or any variable, really—to devalue the lives of others to compete. And this has played out in everything from genocide at the worst end to just everyday social mistrust at the low end.

America—unlike most places, which have defined the concept of a nation around an ethnicity—has tried to do something different. You can come to this country and be any race, color, or creed, and define yourself as an American. This is a fragile experiment. It’s not an easy experiment. It’s something without precedent. And one of the challenges is that we all have to figure out how to live with each other and trade with each other and befriend each other and so forth without succumbing to our worst tribal instincts. Some of it is inevitable. But the question is: How should the state minimize this?

Now, the answer that arose during the civil rights movement, from people like Martin Luther King, Bayard Rustin, and going back to A. Philip Randolph, was essentially that the state should not make any laws that take race into account one way or the other. You should not try to discriminate against people really for any reason. You should not try to discriminate to repay people for past discrimination. There should be something which David Bernstein called the separation of race and state. In the long run, this is the best way to govern this fragile experiment.

People now reject the idea that colorblindness is even possible. Can you explain why you disagree with that?

First, I would concede that most of our ideals are unattainable. If I were to sit here and say, “I want a peaceful society,” no one would mistake that for the belief that we will actually get to a society with zero murders per year. It’s never happened. Right? We take that as a kind of North Star that guides us when we are choosing between A and B, whether in life or in public policy.

I view colorblindness the same way. I’m under no illusion that humanity will completely eradicate the racial tribal instinct or racism or bigotry itself. But I feel that colorblindness, it’s the North Star that we should use when making decisions about public policy, interpersonal, and so forth.

In the ’60s, there was a consensus for a short period of time that colorblindness was the way to go. Shortly after that, the country experienced massive rioting, the likes of which was basically not seen again until Rodney King and then 2020. In the ’70s, something started brewing in the academy called critical race theory, the brainchild of Derrick Bell and Kimberlé Crenshaw, which basically agreed with the white supremacists on the fundamental idea that race is always going to be everything: These naive people that think we can aspire to something higher than being obsessed with race are exactly that—they’re naive. The only thing you should do in life is hunker down into the tribe in which you were born and try to get as much power as possible.

What do class-based programs look like? And how do they compare to race-based programs?

I overuse the word class. It’s not really precise. Socioeconomics in general—how much money you make, income, and wealth—is a much closer proxy for disadvantage than racial identity. In other words, if you pick 10 people from the country at random, from Kansas, from New York, from wherever, and you wanted to rank them by privilege, it’s wiser to use their socioeconomics than to assume that the black people are at one end and the white people are on the other. By using socioeconomics, you’re getting closer, imperfect as well, but much closer to what we mean when we say someone is disadvantaged.

What are the types of programs that you envision that would be helpful to make society better?

As a philosopher, I have the luxury of painting the abstract picture without filling in all the details. But look, there are already social programs that are far more widely subscribed and popular, like the earned income tax credit and need-based financial aid in colleges. I’m not going to argue that they’re perfect, but they’re based on a scheme that is generally more correctly identifying the people that have less advantage than the regime of race-based policies that has become normalized over the past 50 years.

How do you view the role of government?

It’s a good question. Truthfully, I found every theory of government to be insufficient, so I’m not a subscriber of any particular theory. I liked Tyler Cowen’s idea of state capacity libertarianism quite a bit, which was basically the idea that markets are fantastic—they are the source of the world’s wealth—but a lot of our problems today necessitate having a very functional state that’s capable of occasionally doing big things and doing them efficiently.

You were asked to give a talk at TED about colorblindness. What happened?

So I don’t know if you’ve heard of the Streisand effect, but basically, Chris Anderson invited me to come give a talk along the lines of what I’ve just been talking to you about. I gave the talk, and immediately onstage I saw a few people that were visibly upset in the room. But largely, the crowd thought it was within the bounds of acceptable conversation.

The next day I start getting some messages saying there’s a group called Black@TED, which is upset by my talk. Hurt, I think, is the word that was used. And I offered to talk to them and they didn’t want to. So on and so forth.

In a nutshell, what happened is that rather than release my TED talk normally, they asked me to agree to a series of kind of strange release strategies where they would tag a rebuttal to the end of my talk in the same video, or a debate that I participated in with someone else would be combined into the video, all of which I thought was unfair, since there were no factual errors. So eventually we agreed that they would release my thing normally and then two weeks later I do a debate with somebody. So I did the debate with Jamelle Bouie of The New York Times.

But Tim Urban tweeted that he’s pretty sure TED was intentionally sandbagging, not promoting, and not amplifying my video, because every other TEDx talk had a minimum 400,000 views, maximum 800,000, and mine strangely had 70,000. The only outlier in the whole batch.

Details aside, the crucial thing is that TED, like many organizations, is caught between a faction that believes in free speech and viewpoint diversity and a faction that believes if you hurt my feelings with even center-left, center-right, or, God forbid, right-wing views, you need to be censored. The same kinds of people who say that speech is violence, who say that they were actually hurt or felt unsafe because of my TED talk, are the same kinds of people right now that see Hamas slaughtering children in front of their mothers and say, “That’s not violence. That’s resistance.”

It’s really a situation of a heckler’s veto. There’s a tiny minority of people that do not believe such views should be heard. They have outsize power. And when people aren’t willing to stand up to it, it can make it seem like they’re everyone.

Did you experience that as a student at Columbia University as well?

Probably my second year, 2017, I had a conversation with someone and we kind of realized there was this moment in college where you sort of come out of the closet with a friend as not “woke.” And you just put yourself out there and you hope to God that they’re also not woke and they’re usually not. That’s the thing. Most of the time, the vast majority of kids on these college campuses are not hook, line, and sinker woke in the sense that they believe speech is violence. But there is a radical fringe—5 percent, maybe 10 percent—that is very loud and very confident.

What draws you to Martin Luther King Jr.?

He’s a rare figure for a few reasons. One is the depth and breadth of his knowledge. He has a great essay called “My Pilgrimage to Nonviolence,” where he explains in detail what it is that he learned from Plato, what it is that he learned from [Immanuel] Kant, from [Karl] Marx, why he rejected Marxism, how he integrated all of the Western European canon into his line of thought, and then also brought with it the Baptist preacher element, integrated all of it in a way that was rigorous and inspiring to blacks and whites alike.

I’m a secular person. I’m an atheist. I can’t bring myself to believe in any of the man-made books. But I believe that secular people want to sanitize the Christian element of Martin Luther King, because to admit that his Christianity was a core part of his success would cast doubt on the hope that secularism can stand on its own two feet.

What do I mean by that? I mean when Martin Luther King got up there and said in Christ “there is neither Greek nor Jew, black nor white, bond nor free,” that made sense and gave goose bumps to the black public, to the white public, etc. He was speaking a language that people understood not just in their prefrontal cortex but in their hearts. There’s no secular equivalent to that statement that really resonates with people to such an extent. And that’s a problem for someone like me who is trying to update in many ways MLK, which is that I’m not a Christian; I can’t speak that language honestly. And even if I could, the country isn’t Christian enough to resonate with it.

Who was Bayard Rustin and why does he matter so much?

Bayard Rustin is one of my great intellectual heroes, probably more so than King even. He was born in Pennsylvania, raised by his grandparents, who he thought were his parents for most of his life. He was a Communist very briefly, and then a socialist and civil rights organizer in the 1940s.

Rosa Parks is remembered for refusing to give up her seat in the front of the bus and go to the back. Many people had done this before Rosa Parks. She was not the first to do this. Bayard Rustin did this 13 years before she did and got beaten to a pulp by the cops because of it. Rosa Parks was just the one lucky enough to make the history books. The country was ready, in other words. So he was right there from the beginning.

He ends up getting involved with Martin Luther King Jr. and helping him start his organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. He organized and led the March on Washington, at which Martin Luther King gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. He read the list of demands at that event, and he was just a beautiful essayist throughout the entire period that very few people know about.

An important fact about why he isn’t known more is that he was openly gay. He was arrested for being caught in a car with a man. And in fact, Dr. King was blackmailed by Adam Clayton Powell who threatened to expose a fictional gay affair between Rustin and King if they didn’t cancel a planned protest at the [Democratic National Convention].

What I really admire about him is that he was more active and more passionate than anyone you could name in American history about getting black people full human rights. But he was also completely clear about the fact that race is not what’s important. And when the Black Power movement came along in the late ’60s and started saying that “actually we don’t want equality, we want more, we believe black people are not just equal to white people, but better,” he was very clear-eyed in saying that this is evil. That this is not just something for radical chic white liberals to pay lip service to; this is an evil on the horizon if we allow it to fester. And he drew that line very clearly in a way that too few people have courage to do.

This interview has been condensed and edited for style and clarity.